Michelle Flynn with her daughter, fourth and third from right Koori Mail 2014 Naidoc

In 2014 Michelle Flynn entered and won a Canberra local radio competition – the prize a tour of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). After the tour she mentioned to AIATSIS staff the battered cricket case which she had inherited on the death of her grandfather Alf (Alfred) Stafford. This was to have enormous consequences. The case which referenced Alf’s enthusiasm for cricket (he bowled the first ball at Manuka oval, Canberra, played Sheffield Shield and played on the same side as Don Bradman) was stuffed with photos, letters and other documents and memorabilia, amongst which was a family tree. The information in this tree showed Alf’s descent from Kitty, known to be a member of the Warmuli (Prospect) Clan of the Darug and one of the children admitted in 1814 to Governor Macquarie’s Native Institution. Kitty later married convict Joseph Budsworth. Not only that, the tree showed that Alf descended from the New South Wales Gamilaroi Blackman family. Although Alf had told his family about his Aboriginality, they had been unaware of its detail and extent. Now examination of information in his (and their) family tree has facilitated an exciting understanding of the family’s place in the Aboriginal history of New South Wales, one which they have embraced with pride and enthusiasm.

Michelle subsequently donated the case’s precious contents (now known as the Stafford Collection ) to AIATSIS. Initially its significance to AIATSIS was in large part the fact that Alf, an Aboriginal man, had worked for eleven of Australia’s prime ministers either as personal driver or cabinet officer, including driving for Sir Robert Menzies, for whom he became a trusted confidant. However the wider significance of the family tree and the opportunities it gave for exploring more of the extended Stafford family were not lost on Michelle, who with help from family members, AIATSIS and others began unpacking the information in the tree and using it to extend and expand her family knowledge, including learning more about the Stafford Blackman connection. This stemmed from the marriage of John Allan Stafford, son of Joseph Stafford and Catherine Budsworth (daughter of Kitty and Joseph Budsworth) to Mary Ann Blackman (daughter of Gamilaroi Thomas Blackman).They were the parents of twelve children, the youngest Michelle’s grandfather. In the investigation process Michelle also found connections to the New South Wales Aboriginal families Cain, Griffin, Chatfield and Talbott.

In one area in particular the information uncovered was unexpectedly rich. A simple search of National Archives of Australia RecordSearch shows the World War One AIF service of Alf’s brothers John Harold Stafford, Charles Fitzroy Stafford and Clyde Gilford Ortley Stafford. Although Alf himself was too young to serve in the first war his cricket case also yielded information about his inter war service in the in the militia.

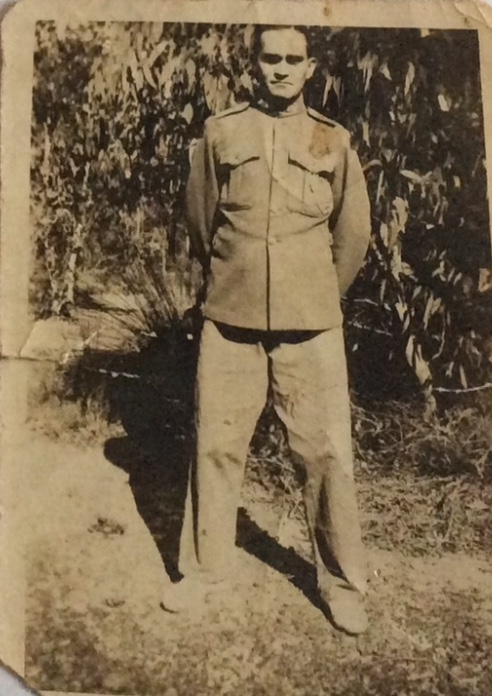

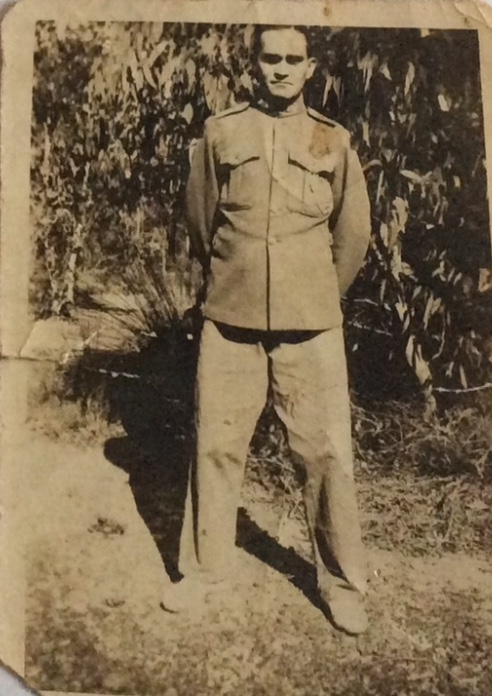

Alf Stafford Holsworthy army camp NSW Courtesy Michelle Flynn, Stafford Collection, AIATSIS

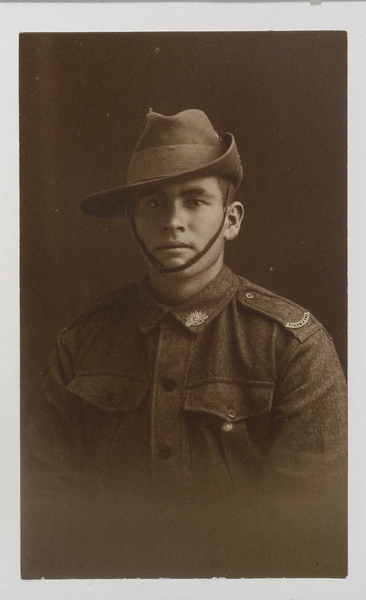

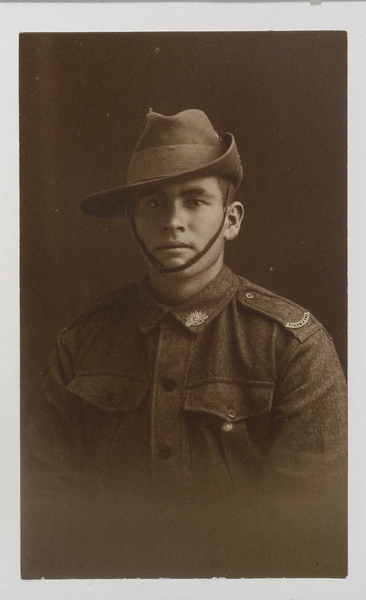

John Harold Stafford (brother of Alf) Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Additional research has led to the discovery, so far, of a total of 29 volunteers for service in the First World War from the extended Budsworth/Stafford/Blackman and connected families – all but three serving overseas. These men are included in the list of men contained in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteers for the AIF: the Indigenous response to World War One, fourth edition, (Philippa Scarlett), published in 2018 – with one exception, Henry George Stafford who served as Joseph Smith. His grandson Bill Reid only recently contacted Michelle to let her know that his grandfather enlisted under an alias and was actually a brother of Walter James Stafford and like him a first cousin of the Stafford brothers.

The service of these men, whose names are listed below, encompasses so many of the elements which make up the experience of all volunteers for the First AIF– the larrikin and other more serious misbehaviours which triggered punishments ranging from a few days detention or fines to the Field Punishment No 1 (being tied to a wheel) experienced by Joseph Smith aka Henry George Stafford as well as the damage to health which was characteristic of most volunteers. Records show that in almost all cases the group’s service was at physical cost to their well-being: they suffered from mumps, malaria and other non specified sickness, lost limbs, were wounded by gun fire and shell fragments, sometimes more than once and were gassed with effects which persisted post war. Some like James Budsworth, wounded and suffering trench fever, were sent home early with medical discharge. Five lost their lives on the Western Front : Roderick Hamilton Budsworth, William Allan Irwin, John Talbott, Joseph William Hamilton, who enlisted as Joseph William Buddsworth and Walter James Stafford.

Roderick Budsworth [alias Rodger Budsworth] State Records of NSW Series NRS2327 Item 3/597

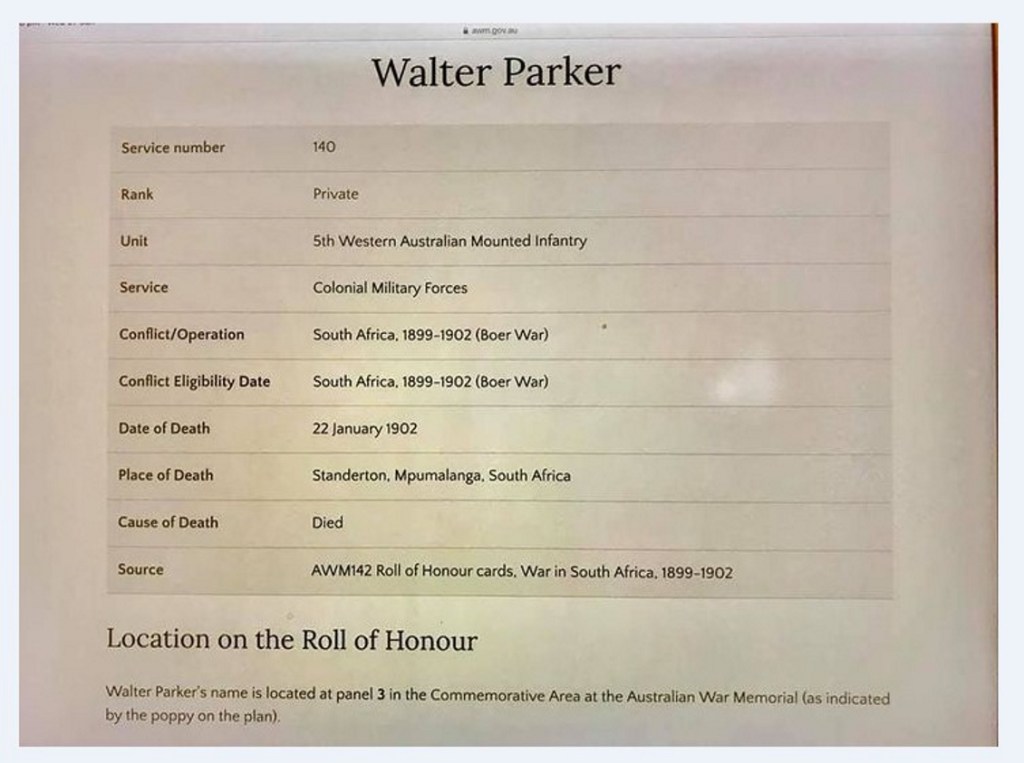

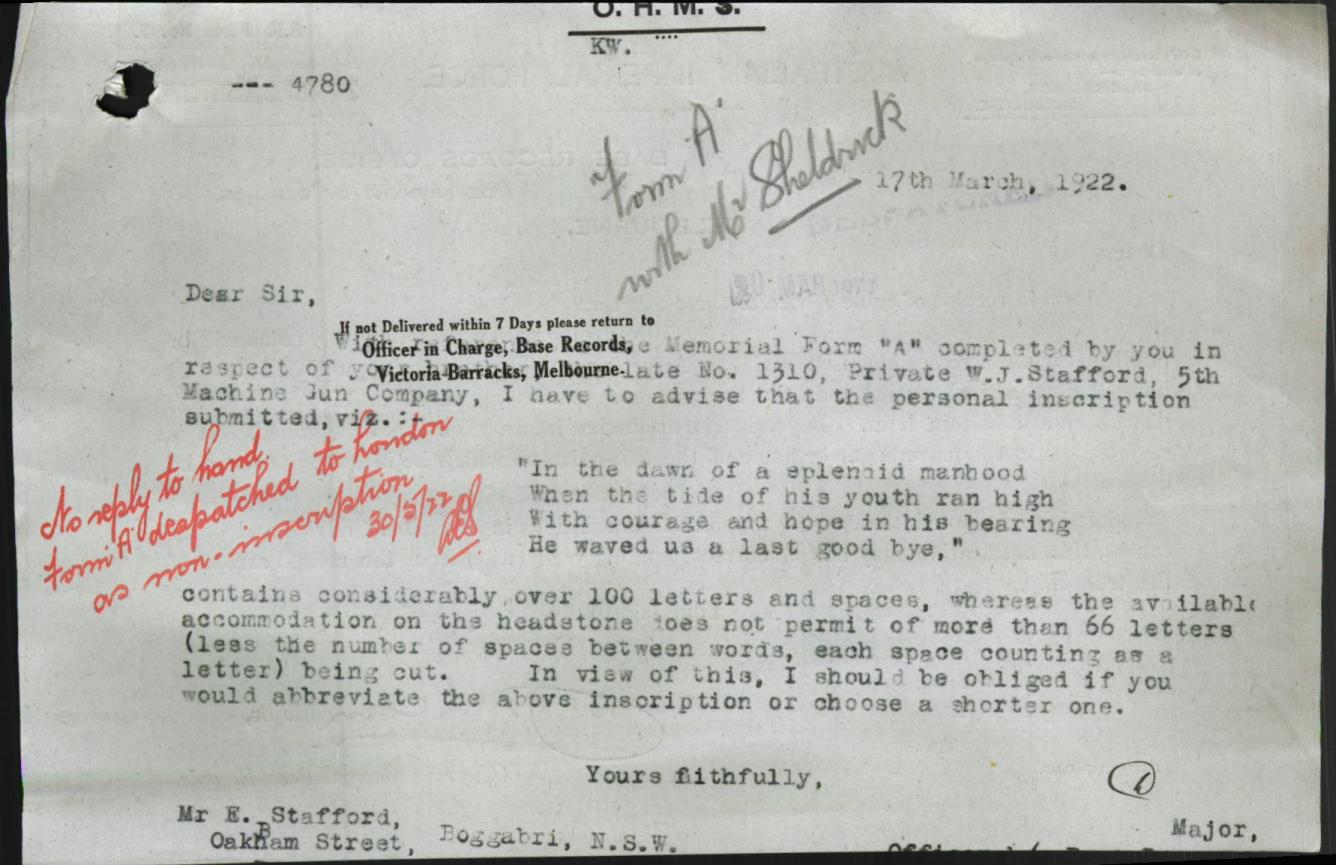

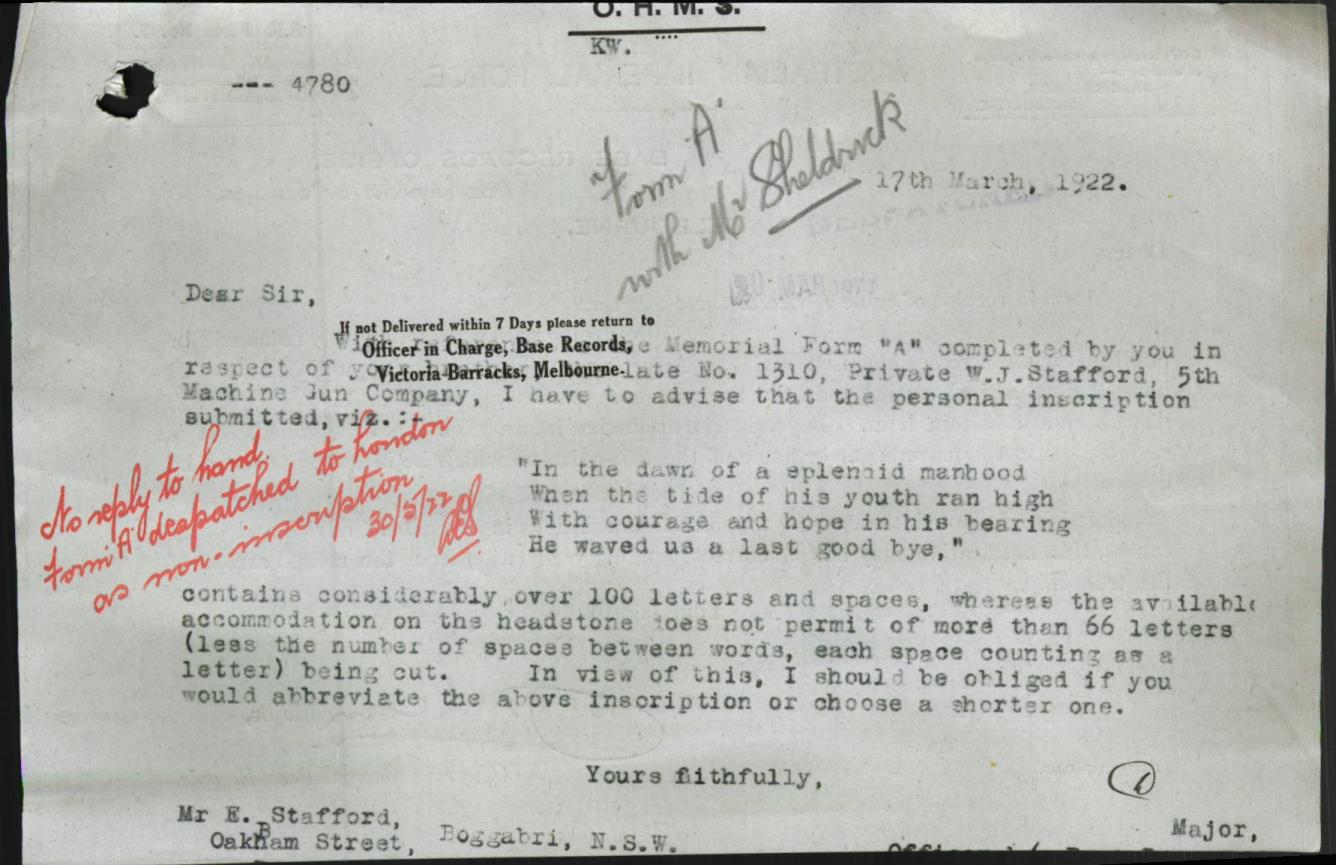

Letter to Edward Stafford about his suggested inscription for his brother Walter Stafford’s headstone. Unfortunately it exceeded the permitted word count. The letter is annotated ‘No reply to hand. Form A despatched to London as non inscription.’ NAA: B2455 WALTER JAMES STAFFORD

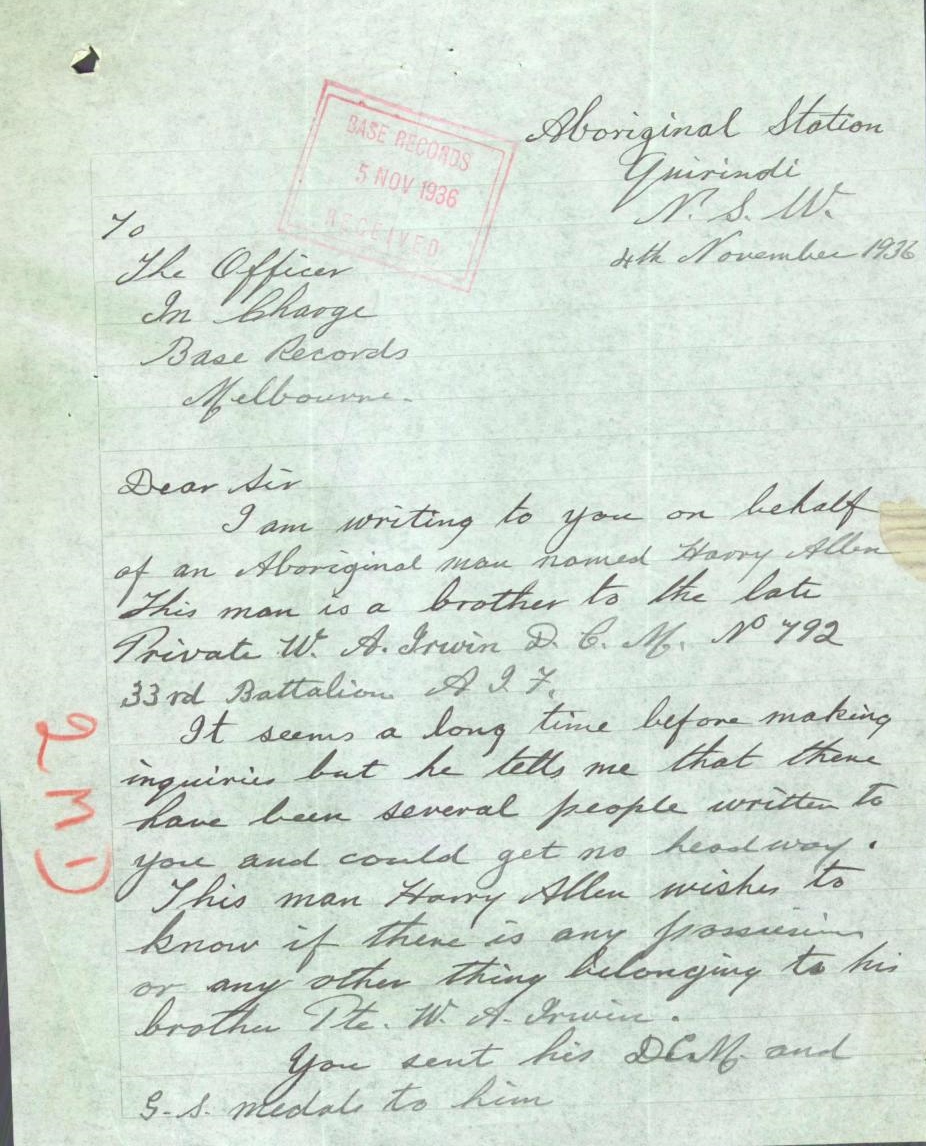

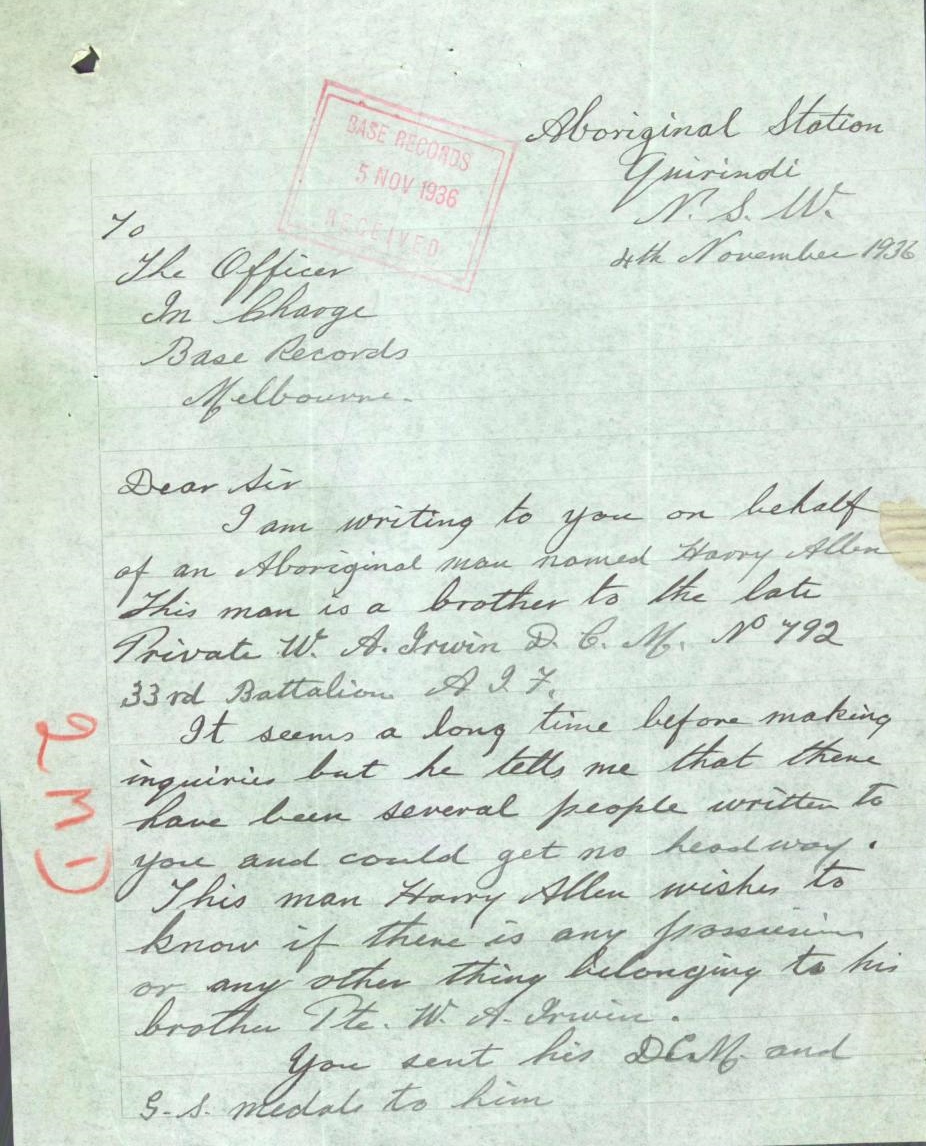

Extract from a letter from the Manager, Quirindi Aboriginal Station in connection with the distribution of William Irwin’s possessions. NAA: B2455, WILLIAM ALLAN IRWIN

William Allan Irwin DCM: the framed photograph kept by his family. Note the lower half of the image appears to have been added to the torso Courtesy great nephew Peter Milliken

William Allan Irwin DCM: the framed photograph kept by his family. Note the lower half of the image appears to have been added to the torso Courtesy great nephew Peter Milliken

William Allan , who enlisted as William Allan Irwin was the only member of the extended family to be decorated. He posthumously received the Distinguished Conduct Medal, one of only four known Aboriginal men to receive this award.

Most of the group belonged to infantry battalions, serving predominantly in France and Belgium but some men were members of artillery units and light horse regiments. The focus of the latter was the Middle East. Two of Alf’s brothers Charles Fitzroy Stafford and Clyde Gilford Stafford served at Gallipoli and Charles Stafford was a member of 12th Light Horse, which took part in the cavalry charge at Beersheba on 17 October 1917.

Charles Fitzroy Stafford (brother of Alf) Courtesy Michelle Flynn, Stafford Collection, AIATSIS

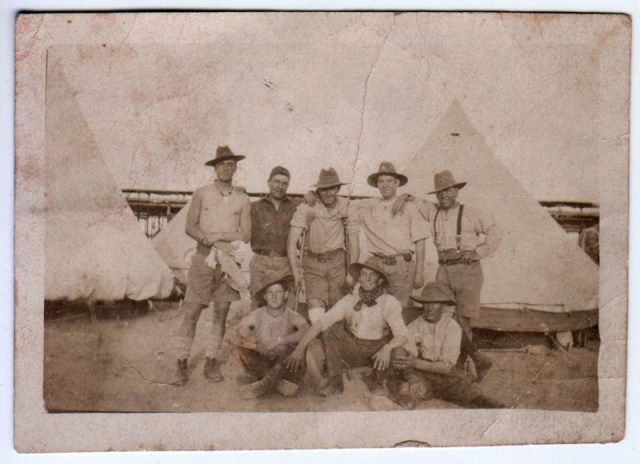

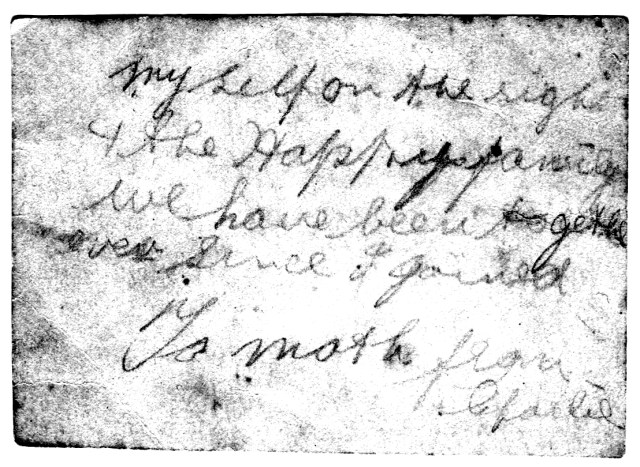

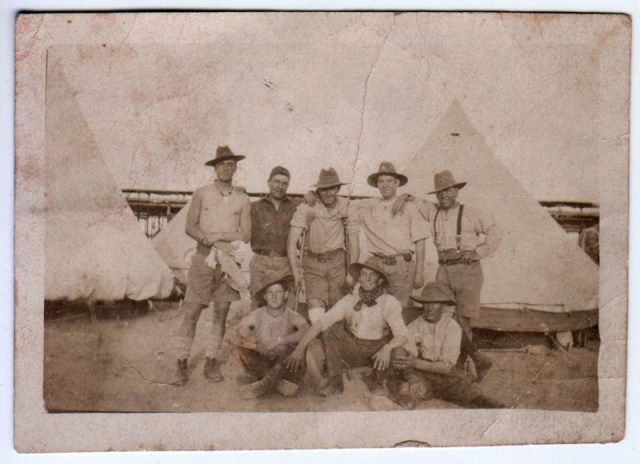

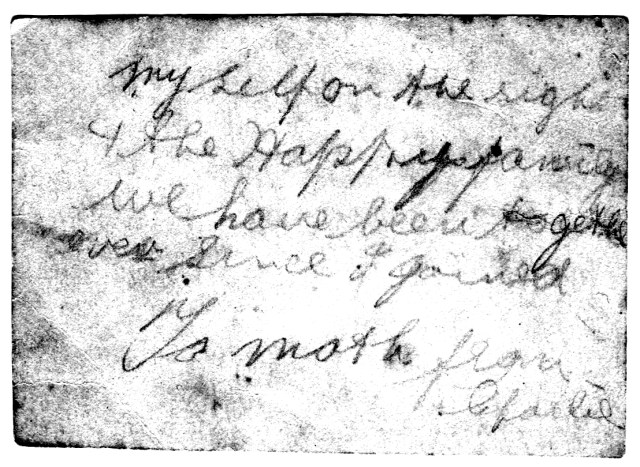

Charles Stafford, Middle East back row right. This snap is from a Stafford family album The reverse reads ‘Myself on the right & the happy family We have been together ever since I joined To Mother from Charles’ Courtesy Diana Griffiths

James Budsworth at 41 was one of the older volunteers. He served with the Light Horse remounts which attracted older men with horse handling experience. The records show that the 29 volunteers ranged in age from the 44 to 18 years but in fact Wilfred Budsworth gave false information and was actually 16 when he volunteered. Of those underage there is evidence of only one instance of the permission of parents being given for the enlistment of their 19 year old son, Ernest John Blackman. Enlistment under other names and spellings – eg Joseph William Buddsworth (Hamilton), Joseph Smith (George Stafford) were possible devices to avoid the attention of parents or close relatives.

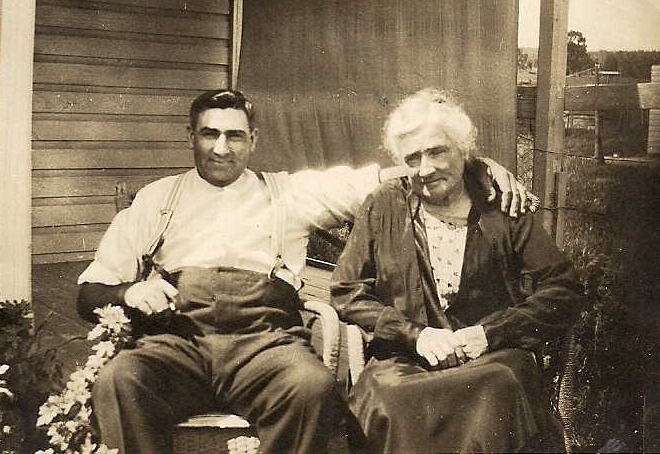

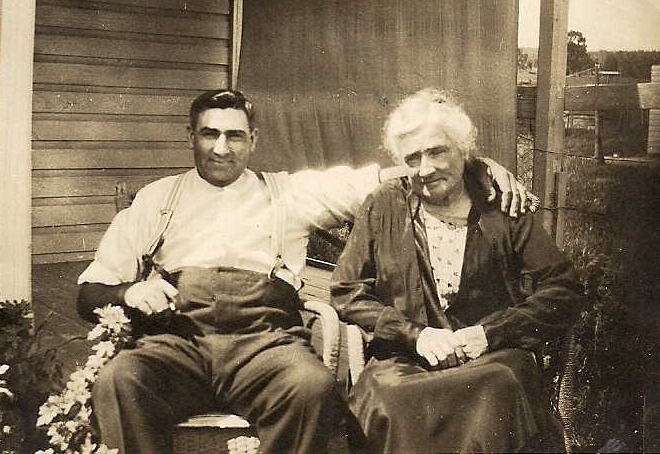

Ernest Blackman who enlisted age 19 with his mother in later life Courtesy Michelle Flynn

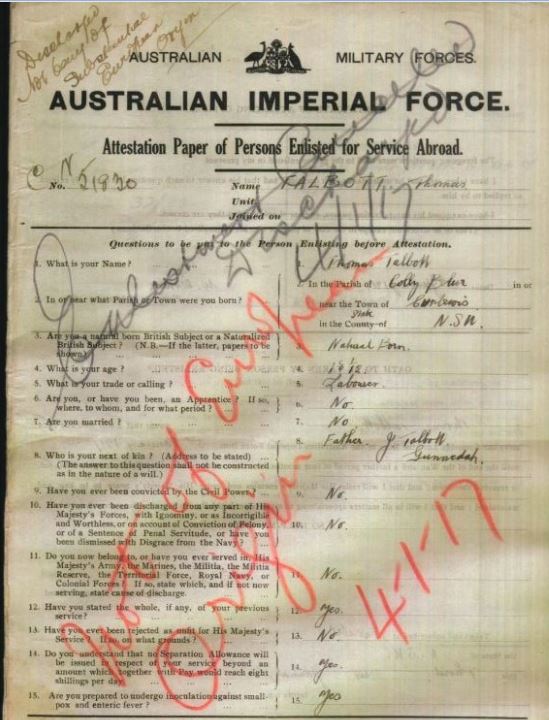

Some like John Harold Stafford and William Wallace Chatfield tried to enlist more than once before they were successful. Of those who were rejected only two were refused explicitly because of their race – (William) Thomas Talbott and William Wallace Chatfield. Chatfield’s successful attempt after initial rejection as ‘unsuitable physique (colour)’ is yet another example of the fact that while it is clear recruiters ignored the Aboriginality of others (something which in some cases is obvious from secondary sources) they were not consistent in their enforcement of the provisions of the Defence Act, which precluded Aboriginal enlistment. This is also clear in the cases of Herbert Hamilton whose service record noted his father was white and mother ‘half caste’ but who still achieved entry into the AIF. It is worth noting this was before a May 1917 military order which allowed the enlistment of men with one white parent.

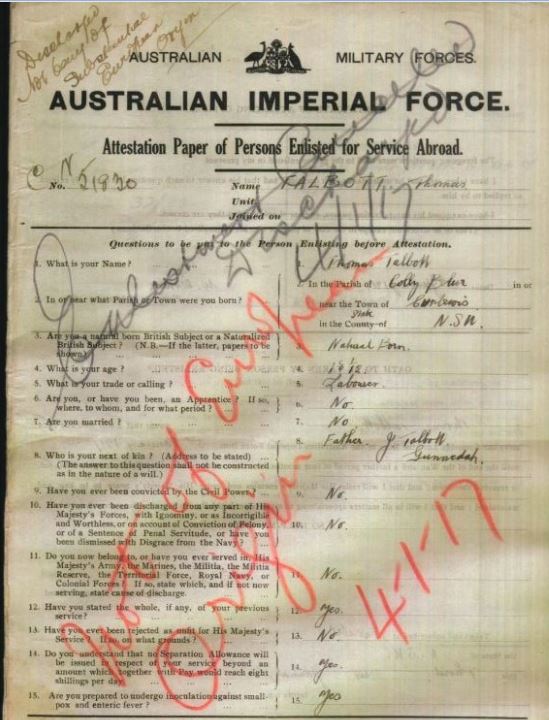

NAA: B2455,TALBOTT, WILLIAM THOMAS.

William Wallace Chatfield Australian War Memorial: AWM2016.641.1

Information given on enlistment locates the extended family predominantly in northern and central western New South Wales and shows that the volunteers came from places like Maitland, Gunnedah, Binnaway, Coonabarabran and Narrabri with others from Inverell and additional New England locations. Most were labourers but occupations included drover, brickmaker, coachmaker, blacksmith, and farmer. The records show the enlistment of brothers – something common to many families and that family members volunteered from early 1915 to late 1918. In two instances, Herbert Hamilton and Ernest Blackman both embarking late 1918, returned to Australia before reaching England, when their troop ship was recalled because of the cessation of hostilities.

Perhaps the most touching object in Alf’s cricket case is the medallion which depicts his three soldier brothers and would have been worn as a brooch by their mother, who with all AIF mothers shared that combination of pride and fear which characterised the feelings of close relatives. Complementing this is a photo of Alf, aged eight which shows him dressed in AIF uniform, indicative of his family’s support for the war.

Alf Stafford aged eight in Light Horse uniform Courtesy Michelle Flynn, Stafford Collection, AIATSIS

Medallion brooch showing the three soldier brothers of Alf Stafford Courtesy Michelle Flynn, now held in the Stafford Collection, AIATSIS

Alf’s careful guardianship of his family history shows his pride in his family and bears witness to his own considerable achievements – as well as opening a window into his Aboriginality. This is augmented by the ability to use the information he saved, combined with external sources, to identify the records of war service of his brothers and extended family – something Alf would have been unlikely to have anticipated. These records, because of the detailed information they contain, deepen the knowledge of his family and form an invaluable source of information about each individual service man, his family connections, where he was born and lived and so much more.

The service details of the family network discovered by Michelle represent a microcosm of the AIF experience. They show that Aboriginal people who served in the AIF had the same range of experiences as the AIF as a whole but that some also encountered the racism implicit in the Defence Act – the rejection of two men on race grounds. It is hard to know to what degree this racism permeated the AIF following enlistment or whether it affected any of the men listed here but examples relating to other men demonstrate that it was not unknown (see Philippa Scarlett in Aboriginal History: Volume 39 2015). What is clear is that the records of these men demonstrate the willingness of an extended Aboriginal family group to serve their country despite the existence in it of racism and the discrimination and disadvantage it engendered.

On 9th March 2019, close to the anniversary of the death in battle of Walter James Stafford, some of the members of the extended family gathered at the Australian War Memorial to witness the Last Post Ceremony commemorating his death – brought together by their family connections and the efforts of Alf Stafford’s granddaughter Michelle and her realisation of the important legacy he had entrusted to her.

.

Some of the extended family who gathered at the Australian War Memorial on 9 March 2019 to commemorate the anniversary of the death of Walter James Stafford (Killed in action 6 May 1916). Courtesy Michelle Flynn

Michelle Flynn and Philippa Scarlett

15 June 2019

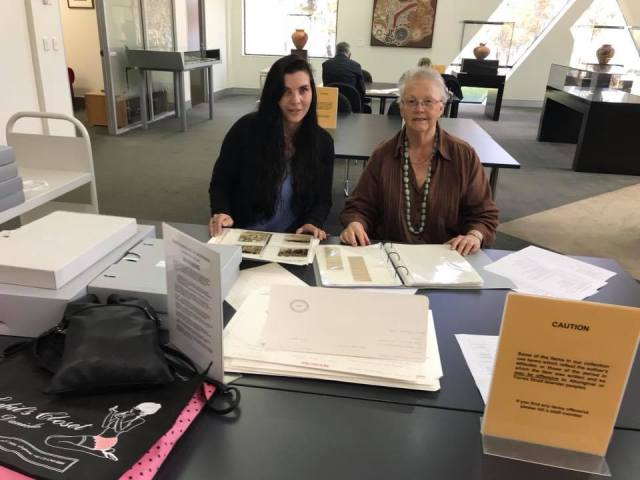

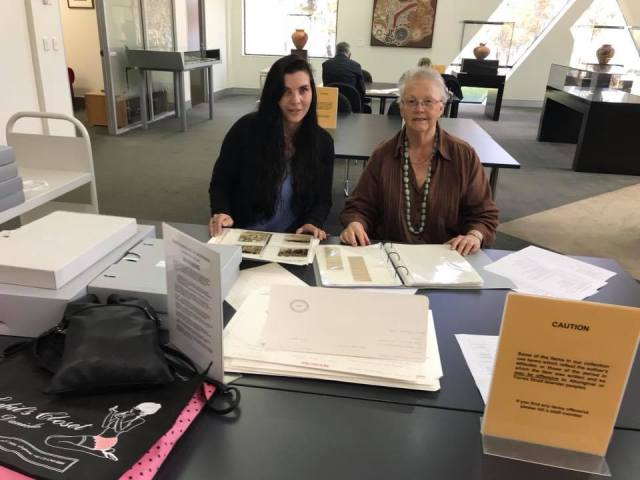

The authors examine the Stafford Collection, AIATSIS

MEMBERS OF THE STAFFORD, BLACKMAN AND EXTENDED FAMILY WHO VOLUNTEERED FOR THE FIRST AIF

Note This is not an exhaustive List. The men have been identified by Michelle with help from family members including Jo Rose, Peter Milliken, Aunty Madge Nixon and Bill Reid. Information about the Stafford brothers is featured in AIATSIS online Exhibition The Stafford Brothers.

NAME, SERVICE NUMBER AND PLACE OF BIRTH

BAKER Walter James Depot Coonabarabran NSW

BLACKMAN Ernest John 67827 Gulgong NSW

BUDSWORTH James 2465 Narrabri NSW

BUDDSWORTH Joseph William 3971A (also known as Joseph William Hamilton) Inverell NSW

BUDSWORTH Joseph 1381 Sydney NSW

BUDSWORTH Robert (known and enlisted as Walter Coleman 388)

BUDSWORTH Roderick Hamilton 18 Coonamble NSW

BUDSWORTH Wilfred Ernest N91395 (Depot) Tamworth NSW

CAIN George William N94566 (Depot 94566) Coonabarabran NSW

CAIN James Edward 3146 Coonabarabran NSW

CHATFIELD Alfred William N/A (Depot) Coonabarabran NSW

CHATFIELD William Wallace 57312 Coonabarabran NSW

COLEMAN Walter John 388 Newcastle NSW

GALVIN William John 1132 Inverell NSW

HAMILTON Joseph. Served as Joseph William Buddsworth 3971A

HAMILTON Henry Claude 3162A Inverell NSW

HAMILTON Herbert 3742 Yugilbar (Copmanhurst) NSW

IRWIN William Allan 792. Alias of William Allan. Coonabarabran NSW

SMITH Joseph 2474. Alias of Henry George Stafford] Gunnedah NSW

STAFFORD Charles Fitzroy 190 Mudgee NSW

STAFFORD Clyde Gilford Ortley 3107 3157 Coonabarabran NSW

STAFFORD George Montgomery 14729 Angledool NSW (Angleedool

STAFFORD John Harold 64759 Binnaway NSW

STAFFORD Walter James 1310 Gunnedah NSW

STAFFORD William Henry 1909 Coonbarabran (Coonabaran) NSW

TALBOTT John 5220 Pilliga NSW

TALBOTT William Thomas N51830 Colly Blue Curlewis NSW

TIGHE Patrick 3313 Mudgee NSW

TIGHE William James 57648 Narrabri NSW

Michelle would like to thank the following people who have helped her find out more about her extended family’s service in the First World War.

Michael Bell

Paddy Chatfield

Christine Cramer

Rosemary Norman Hill

Rita Metzenrath

Peter Milliken

Mark Muliet

Madge Nixon

Joy Pickette

Philippa Scarlett

Jo Rose

Bill Reid

Dolly Talbot

SOME USEFUL SOURCES

AIATSIS, https://aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/stafford-brothers

Indigenous Histories, https://indigenous-histories.com/2013/10/29/walter-budsworth-coleman-aif-member-and-warmuli-clan-descendant/ ; https://indigenous-histories.com/2013/02/06/aboriginal-writing-letters-and-documents-in-ww1-service-records/

Marg Powell, Des Crump, State Library of Queensland http://blogs.slq.qld.gov.au/ww1/2017/11/24/james-budsworth-2485/

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. New South Wales officers and men of the Australian Imperial Force (A.I.F.) and the Australian Naval Forces: portrait collection, 1919. Crown Studios. P1/ Servicemen (BM). (portrait of John Stafford)

National Archives of Australia. Australian Imperial Force, Base Records, B2455 Personnel dossiers for first Imperial Forces ex-service members, lexicographical series.1 Jan1914 – 31 Dec 1920.

National Archives of Australia. Australian Imperial Force, Base Records, MT 1486/1, Applications to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force.

National Archives of Australia. Australian Imperial Force, Base Records, B2455 Personnel dossiers for first Imperial Forces ex-service members, lexicographical series.1 Jan1914 – 31 Dec 1920.

National Archives of Australia. Australian Imperial Force, Base Records, MT1486/1, Applications to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force.

Joy Pickette Footprints in the Sand. Stories of Aboriginal soldiers in the First World War who had a connection to Coonbarabran, Coonabarabran DPS Local & Family History Group Inc. 2017.

Philippa Scarlett Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteers for the AIf: the Indigenous response to World War One, fourth edition, 2018.